Time to say good-bye to the Olympics you know

It’s time to say ‘good-bye’ to the Olympic Games you know and say ‘hello’ to the Games you have proven you want. Guest contributor Malin Dunfors gives us Part 1 of a three-part series on how action sports have turned the Olympic Games on its head.

“I don’t know, can the Olympics handle it?”

It’s a valid question: Can the Olympic Games handle the progression and obvious popularity of more and more extreme sports joining the programme?

There may not be a choice.

Reflecting on whether mountain bike slopestyle will be next in line to break into the Olympic Games, joining other traditionally extreme sports such as snowboard and BMX, cameraman/photographer Dan Campbell-Lloyd concluded it would probably end up being the best thing to watch.

“That and table tennis,” he said wryly.

Over ten days of extreme action in Whistler – at the world’s biggest festival of its kind — some of the best slopestyle, enduro and downhill riders in the world descend on the mountain resort to push their sport to new heights. And they’ve been doing it for a decade:

Repeat: Push to new heights.

Sound familiar?

Halfpipe skiing? Check. Slopestyle skiing? Check. Slopestyle snowbard? Check.

All three envelope-pushing sports will attract the world’s attention as official debut events on the Sochi 2014 schedule.

Sure, certain action sports are undeniably contagious, they ‘push to new heights’ garnering consistent international media attention. But they had to start somewhere, and the sad truth is many extreme-sport beginnings also face extreme ends.

Here’s a look at a few extreme-sport fads for which equipment is now collecting dust in basements everywhere.

TOP 7 ACTION SPORTS THAT FLOPPED:

YOUNGER, FASTER, COOLER

The Olympic Games and extreme sports might sound like an odd couple indeed – non-conformity, rebellion and free spirit versus tradition, uniformity and status quo. But as sports history made clear, opposites do attract.

Windsurfing became the first extreme sport to be introduced the Olympics in 1984, followed by mountain biking in 1996, snowboarding in 1998 and BMX in 2008. At the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, Russia, less than seven months away, both slopestyle skiing and snowboarding will join the Olympic family.

“One reason that the IOC [the International Olympic Committee] is moving to fringe sports — if that’s what we call them, coming from the X Games environment — is to bring a new demographic that the IOC finds it is losing into the Olympic fold,” says Associate Professor Scott Martyn at the University of Windsor, who specializes in the historical evolution of the Olympics.

During the last 20 odd years, the IOC, which has been referred to as an “eighteenth-century gentlemen’s club,” has seen a demographic shift among its core audience.

As baby boomers are getting older, their children and grandchildren, many of whom grew up on skateboards, roller blades and twin tips, have redefined the framework for the modern Olympic Games.

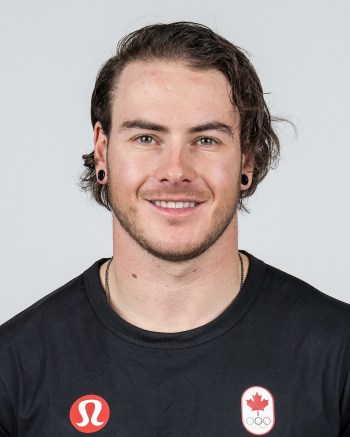

World-beating slopestyle snowboarder Mark McMorris has balanced both a lucrative X-Games circuit and Olympic Games preparation. Photo: Sven Boecker

Add the X Games, a 24/7 news cycle and social networks to the equation, which have created a constant demand for fresh content. The old Olympic motto of, “citius, altius, fortius,” (swifter, higher, stronger) might be in for a revamp along the lines of, “younger, faster, cooler.”

What does this mean for today’s, and tomorrow’s, Olympic movement? And more importantly, how does Canada fit into this new Olympic world order?

IN THE REARVIEW

Let’s start at the very beginning — at the ancient Games.

How do extreme sports of the twentieth-first century compare to old school Olympic standards?

They’re dangerous, but by no means brutal, according to Professor David Gilman Romano, Karabots Professor of Greek Archaeology at the School of Anthropology, University of Arizona.

“If you were an ancient athlete and you went to the gymnasium, the team hall, and you told your mother that you were going to go out for the pankration, she probably would not be happy,” says Romano over the phone line from Greece.

No wonder, pankration, the ultimate athletics event of its day, was characterized by its ferocity.

“A combination of boxing and wrestling in a general free-for-all,” Romano says, where the only rules were no biting or gauging of eyes.

First introduced in the Olympic Games in 648 B.C., casualties were common and Arrhichion of Phigaleia died while claiming the Olympic title.

Still, by and large the ancient sports were rather conservative, each featuring a distinct beginning, middle and end. That is, they were pretty much the same events for more than a thousand years. The ancient Olympic Games included a total of 23 events, but most were actually introduced during the first 300 years of competition.

The Olympic Flame burns in a caldron outside the Parthenon on top of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. Photo: The Canadian Press

The old Greeks also did not differentiate between amateur and professional athletes. Every competitor was called an “athlete,” which literally meant, “to compete for a price.”

GOING PRO

Fast-forward to Crankworx Whistler 2013, where both amateur and professional riders competed on Whistler’s sun-soaked, dusty trails.

The Bishop sisters stand at the bottom of the Whistler trail, sweat, dirt and happy faces. The two keen amateur riders from Seattle, Wash., came up for the weekend to see what the festival is all about.

“For most of the world, and certainly where I’m from, it’s not something that you get exposure to,” says Amanda.

A sport needs to move beyond its grassroots, otherwise it becomes a death sentence, says Rachel and adds, “for a sport to really grow and thrive, and become mainstream, you really need to expose people to that passion.”

Exposure, indeed.

Ryan Meyer, a former competitive rider and Crankworx sport announcer, suggests that it’s the universal recognition that brings additional benefits to various action-sport communities. More sponsors equals more income for the athletes, which in turn allows them to build training facilities in their backyards or elsewhere.

“It means a lot of television coverage, which pretty much bumps up everything else, (like) sponsors,” says Meyer.

“Sponsors have lots more money in their marketing budgets when they see that we’re televised,” says the Vancouver native, who’s dressed in black coupled with a mean mustache. “It’s huge exposure to the entire world … It just spirals and spirals,” notes Meyer. “We’re praying that the X-Games invites us back in again for a second year and that it blows up, but I think it is quite a sport that when people actually witness it, it is very, very good.”

He acknowledges that many extreme sports, especially the judged events, have a hard time breaking into the Olympic programme, yet Meyer’s optimistic about a future inclusion.

“It would be huge for the sport and I’m sure everyone would back it,” he says.

Quebecois downhill mountain biker Yann Gauvin agrees, “It would be a great sport for sure and it has its place there.” Yes, on a second note, “it has to be in the Olympics because it’s everywhere but not in the Olympics.”

For Canada, a future Olympic debut would bring good news. Gauvin, who’s having a year off and coaches biking young guns, emphasizes the breadth and depth of the next generation.

“Lately, a lot of young guys have trained hard and they want to push in the sport, either slopestyle or downhill,” he says. “I think Canadians will be good in a couple of years, especially with Steven Smith who’s really good in downhill.”

Smith ended up taking his third consecutive win at the Canadian Open DH on the final day of Crankworx.

Suddenly, teaching our kids to huck themselves off a ramp at full-speed down the side of a mountain is a very feasible Olympic investment – in all kinds of sports.

Rebels with a cause: how the X-Games changed the Olympics – Pt. 2.