Former ski jumping star on a mission to revive his sport among his First Nation

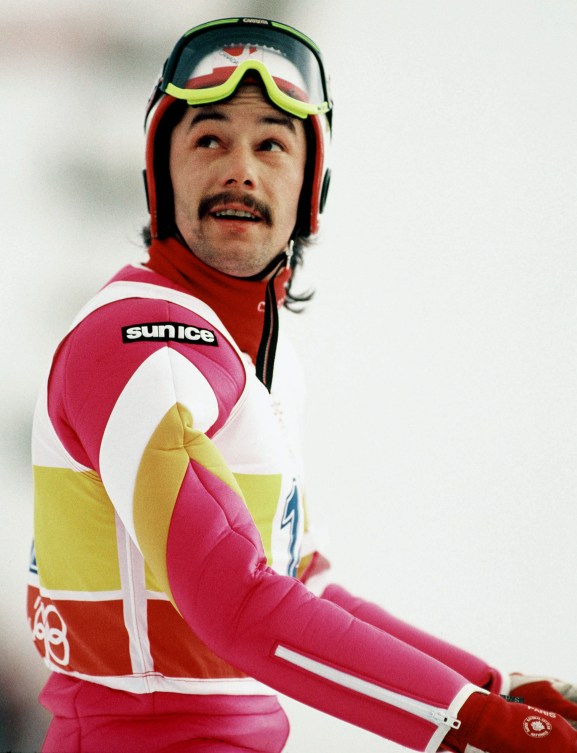

Things have come full circle for legendary Canadian ski jumper Steve Collins.

More than three decades ago, he was a trailblazer in his sport. In recent weeks, he welcomed two of Canada’s newest ski jumping stars to his hometown in northern Ontario – a visit he hopes will inspire the local Indigenous youth to take up the mantle.

A three-time Olympian, Collins’ passion for ski jumping was ignited in the 1970s on Mount McKay, located on the land of the Fort William First Nation where he grew up. Like many kids in the area, Collins got into playing hockey. But at age 11, once he started flying off the built-up snow jumps on Mount McKay, he knew where his athletic future was headed.

“After school, every time I got off the bus I’d run over there before it got dark and jumped,” recalled Collins, who admitted he had no fear. “I just loved doing it.”

The ski jumping prodigy quickly moved onto the then-recently-opened Big Thunder Ski Jumping Centre in nearby Thunder Bay—and hit new heights faster than anyone could have imagined.

Hitting the international scene

He joined the World Cup circuit during the 1979-80 season as a 15-year-old and got to compete in major international events at Big Thunder in January 1980. The following month, he headed to Lake Placid and became an Olympian, an experience highlighted by his ninth-place finish in the men’s large hill event. Collins would earn his first World Cup win in Lahti, Finland that March, not long after being crowned world junior champion.

Collins went on to compete at Sarajevo 1984 and Calgary 1988 and, alongside friend and teammate Horst Bulau, ensured that Canada had a steady, successful presence in elite international ski jumping for a decade.

He returned to Fort William once his competitive career was done and played a big role at the 1995 World Nordic Ski Championships, hosted at Big Thunder. It was just the second time the event had been held outside Europe and Collins was given the honour of lighting the official flame.

But ski jumping’s momentum in Canada was stalled when, just a year later, Big Thunder was abruptly shut down. It left the facility in Calgary, built for the 1988 Olympic Winter Games, as the only place for Canadian ski jumpers to train at home. In 2018, that venue closed as well, forcing the national team to find a year-round training base in Europe as they worked to qualify for Beijing 2022.

A big surprise in Beijing

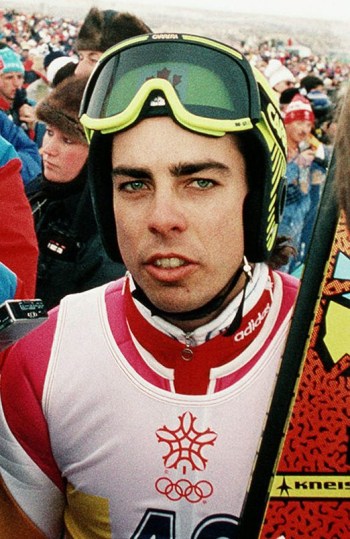

So, it was an incredibly welcome surprise when the quartet of Mackenzie Boyd-Clowes, Matthew Soukup, Alexandria Loutitt and Abigail Strate won bronze in the mixed team event in Beijing.

Collins says he “jumped over the moon” when he saw Canada’s first ever Olympic ski jumping medal unfold.

“It was just amazing,” he says. “I talked to [Bulau], he said he was ecstatic. This is our pride and joy. It’s our life.

“When you have somebody like Mackenzie, he’s the oldest of all the jumpers, experiencing his fourth Olympics, there’s nothing better than to have a medal around your neck, finally.”

READ: The medal that could propel Canadian ski jumping

Collins is hoping the result will not only help rebuild the sport in this country but, more specifically, help feed the dreams of young kids in Fort William.

Olympians inspiring the next generation

To that end, Collins helped bring Boyd-Clowes and Soukup (and their Olympic medals) to visit Fort William in late May.

The event included a smudging ceremony and a speech from Willie Littlechild, a long-time advocate for global Indigenous rights and a member of Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame.

It also featured a Q&A session with local youth and hours’ worth of autograph signings by the Olympic medallists.

“These kids were just overwhelmed with happiness,” says Collins. “Very exciting.”

Boyd-Clowes and Soukup also got a chance to visit Big Thunder, the place where Collins worked to turn his ski jumping dreams into reality. While he says it was “shameful” to close Big Thunder back in 1996, he’s been working to make sure today’s youth get opportunities similar to what he had.

For several years, he’s worked with the owners of Mount Baldy, north of Thunder Bay, to build small, 20-metre jumps out of snow to give kids a taste of the sport in a fun atmosphere.

“It’s just amazing how easy it was to get kids interested,” he says. “They’re on the hills, they have jumps all over, they have rails all over and they just wanted to try it out.”

Building excitement in First Nations communities

Though they don’t yet have the proper equipment for ski jumping, Collins hopes these events will build awareness and excitement not just in Fort William, but in surrounding First Nations communities as well.

It appears to be working. When Collins saw one youngster asking Boyd-Clowes and Soukup some astute questions, he recognized him from one of those days on the hill.

“This kid literally walked up the hill with his skis on, nonstop, nonstop — and he kept jumping to the bottom, to the bottom,” says Collins.

“This kid here could be world champion in five years, he’s so good.”

Whatever the future may hold, it’s clear that Collins and his fellow Olympians have given a new generation of ski jumpers the permission to dream big.